Thanksgiving Turkeys

Aside from being a yummy holiday treat, Thanksgiving turkey is a term used (in North America, at least) to refer to ski racers who come out of the gate kicking everyone’s pants off in November or December and then fizzle out for the rest of the season. Â A friend urged me to write a post on this subject recently, so here it goes…

If you’re unfamiliar with high level ski racing, you might need a little background. Â The way that elite training works is usually built around the fact that the big, important races that you really want to be skiing fast for are later in the season in February or March. Â That means that skiers try to structure their training through the first part of the racing season such that they get steadily faster. Â The concern is that if you go into the ski season in November already “peaked”, it can be very difficult to maintain that level of fitness for the next 2-3 months and you end up “burning out”. Â There’s lots of complicated physiology and training principles at work here, that I’ll likely get wrong if I try to explain. Â So let’s just accept that this is a real concern and leave it at that.

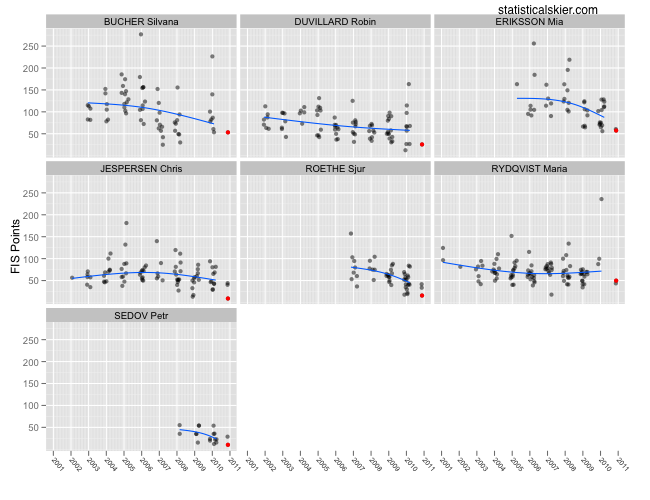

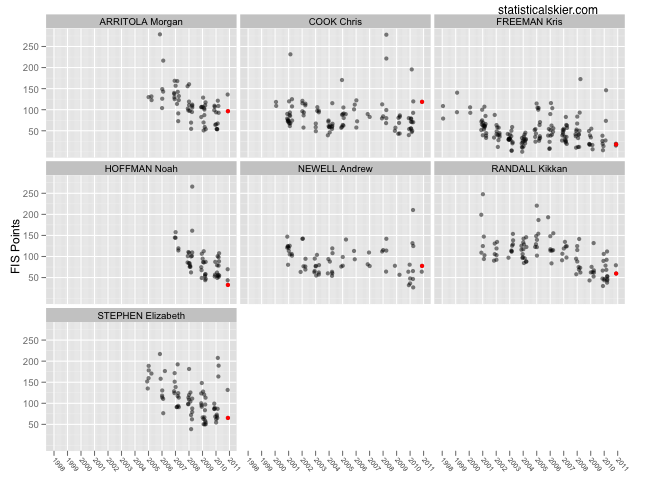

I’m not here to dispute the idea that this happens. Â If you go looking for instances of skiers going really fast early in the season and then flaming out later on, you can certainly find them. Â (And I’ll do just that later on in this post.) Â The “statistics” question here would be whether there’s an overall trend. Â Do skiers who go really fast early tend, on average, to end up skiing really slow later on?

Color me skeptical. Â There are a variety of issues here:

- Reversion to the mean – Skiers who go unusually fast are likely to slow down, not because of some “Thanksgiving turkey” effect, but simply because your subsequent performances are more likely to be closer to your average level of performance.

- How do we define fast? – When we talk about skiers who are “going fast” in November are we referring to skiers beating their competitors or outperforming their own past performances?

- Normal variation and small sample size – As I’ve remarked on before, skiers are not robots. Â Their performances vary quite a bit from race to race, and this is in fact normal. Â Comparing early and late season races for a single racer will involve comparisons of, at most, groups of 5-7 races. Â More often we’ll see someone doing 2-4 races in November/December and then 6-8 in January-March. Â Given the normal variation in racer’s performances, it might not be unusual at all for them to pop a great race in November, which might not mean anything at all.

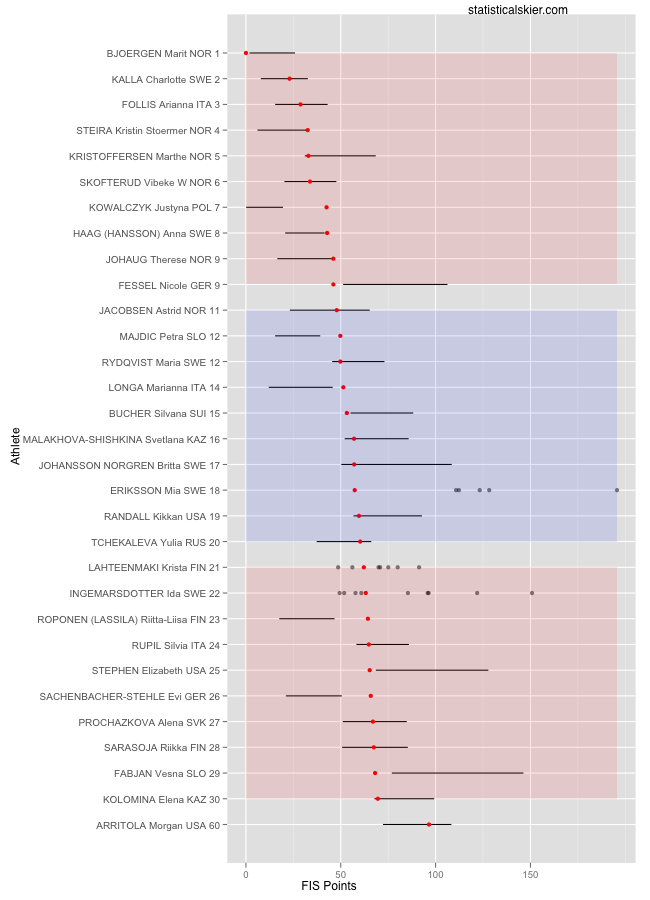

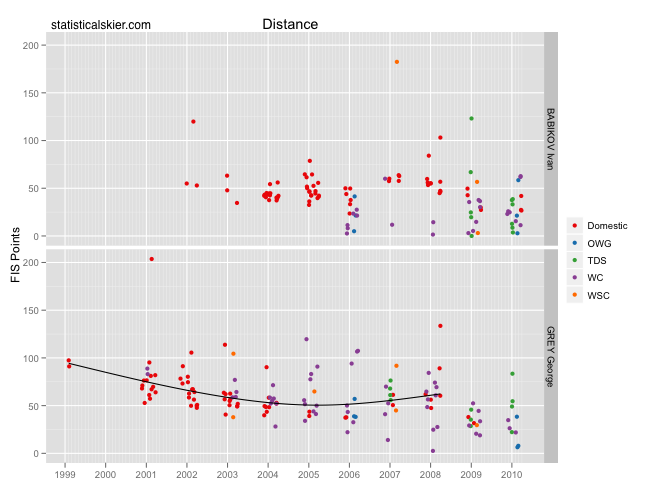

All this will make any general trend very difficult to discern, but let’s see what we can see in the data. Â Since comparing performances within athlete (going fast relative to your previous self) is quite a bit more complicated, I’m going to stick with absolute comparisons. Â The other headache in this investigation is deciding what group of skiers to look at. Â Do we only want to consider skiers with a podium in Nov-Dec? Â A top 5? Â Top 20? Â All of these things are possible, but to prevent this post from spiraling out of control, I’m going to just use FIS points.[1. I’ve tinkered a bit with looking at finishing place, restricting by different subgroups, and I haven’t noticed anything significantly different than what we get with FIS points. Â But there’s an endless number of ways to slice this and I’m sure I haven’t covered them all.]

Focusing on distance results, I divided the season into two halves: Nov-Dec vs. Jan-Mar. Â Then for each athlete and each season I calculated some relavent summary statistics on their results for each half of each season. Â First, let’s look at the median FIS point result in Nov-Dec vs. Jan-Mar: Continue reading ›

Tagged early season, espen rotchev, Fun Stuff, peaking, tor arne hetland