Is There A Home Snow Advantage?

The folks at Nordic Commentary Project were kind enough to point me towards an interesting book that raises the issue of ‘home snow advantage’. I actually haven’t had a chance to read the book yet, but the question of a home snow advantage is certainly an interesting one and it’s one that I haven’t talked about.

The idea that skiers tend to perform better on their ‘home snow’ is an intuitive one, and there is likely something to it, regardless of whatever we may or may not be able to show statistically. But showing it with data is going to be tricky, and involve honest-to-goodness modeling, rather than just a cleverly made graph.

For starters, I’m only going to address distance skiing in this post. This turned out to be complicated enough that I wanted to report back before I spent another few days slogging through a version for sprinting. Next, we need to think carefully about how to model this:

- I only have data at the scale of nations for both location of race and the nationality of the skier. So ‘home field advantage’ is going to be defined as racing in the nation you are from. Skiers changing nationalities happens rarely enough that I’m going to simply wave my hands and declare it to be not a problem. Feel free to disagree.

- I’m only going to consider World Cup races, not OWG or WSC. It’s possible I’m being overly cautious, but I worry that those major events will often be the primary focus of athletes, and this will influence their performance in a way that’s unrelated to where these races happen to be held. I’ve also restricted this to seasons from 2002-2003 onward.

- Not everyone has the opportunity to race both ‘home’ and ‘away’. Obviously, only those athletes from nations where WC races are held have this option at all, and even then, not all of them actually do. So I’m only considering those athletes that have raced both home and away at least three times each.

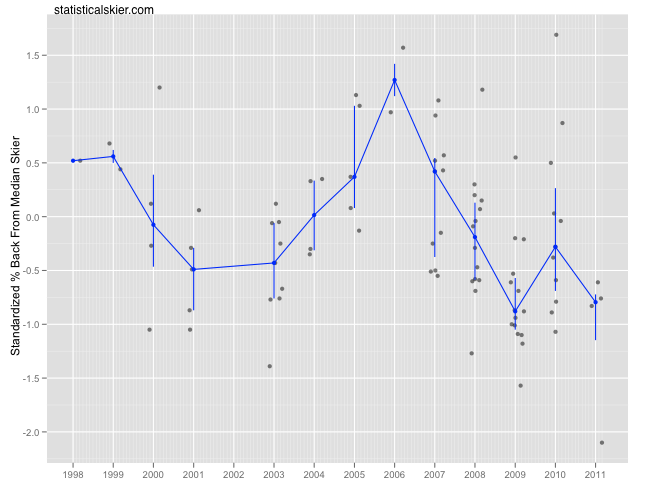

- What’s our response variable? Namely, how do we measure differences in performance for a skier at home versus away? What I settled on was to take the standardized percent back from the median skier and then adjusted it so that it measures the performance relative to that specific athlete, at that point in their career. So I am controlling for differences in performance across athletes and also differences within each athlete over time.

- What are our explanatory variables? I’ve included a Home vs. Away variable, of course, and also gender, nationality and a variable that roughly accounts for some of the wider discrepancies in field strength.

I used some fancy modeling techniques that allow me to estimate the Home vs Away effect separately for each athlete and also for each nation. Keep in mind that lots of athletes (and whole nations!) are being tossed out completely because so many folks haven’t actually raced both home and away. In particular, I made the (possibly contentious) decision to not to consider Canadian WCs as ‘home’ races for Americans, so the US doesn’t appear in this analysis at all.

Once I felt like I had a model that fit as well as I was going to get, I extracted information on a few athletes that had the largest Home vs Away splits in each direction. That information appears in the following table: Continue reading ›

Tagged Analysis, home snow advantage