Podium Development – Sprinting

As promised from last time, here we have the detailed development plots for sprinting. First the men:

And the women: Continue reading ›

Tagged development, men, Sprint, women, World CupAs promised from last time, here we have the detailed development plots for sprinting. First the men:

And the women: Continue reading ›

Tagged development, men, Sprint, women, World CupAs promised from last time, I’m going to show you the un-aggregated data from Tuesday’s plots. This means we’re going to have some big graphs, bigger than I typically think is useful, but no matter.

I’ve plotted FIS points versus age for each of the male and female skiers with a podium result in a major international competition, and indicated the age at which each skier attained their first WC start, their first points and their first podium. If you only see two (or fewer) vertical lines, that means that some of those events happened at basically the same age. (Keep in mind that my age data is only at the resolution of a whole year.)

First the men’s distance podium skiers (these are big; click through for full versions): Continue reading ›

Tagged development, Distance, men, women, World CupI happened to be thinking about visualizations of athlete development recently, and in the process cooked up the following graph:

What I’ve done here is to take the podium finishers in major international events for the past five seasons and recorded each person’s age when they received their first (individual) WC/OWG/WSC start, when they scored their first WC/OWG/WSC points (i.e. a top thirty at any of those events), and finally when they first landed on the podium.

The style of graph here is sort of a more informative type of boxplot. Boxplots really only show you five values, so there’s a lot of lost information. Here, each dot represents a single athlete, so we can get a sense of the entire distribution of ages for each event.

As expected, the women’s ages tend to be somewhat lower across the board; this could be development related, but I tend to ascribe it as much to differences in field depth or competitiveness. The basic story is roughly the same in each of the four panels: rarely do future podium skiers get their first “major” start after the age of 23, they finish in the top 30 after at most a year or two, and then finish in the top three maybe another 2-3 years later.

Of course, that’s what happens with the “average” skier, which doesn’t exist. We are all our own unique snowflake. So this is still masking a fair bit of variability (that I’ll delve into a bit more on Thursday). But the basic lesson I draw from this is that if there’s a threshold to be seen here, it’s at the age of 25. The best skiers seem to have established at least the potential for scoring World Cup points before the age of 25.

Tagged development, Distance, men, Sprint, women, World CupA curious report surfaced a while back that included some doping allegations around Juha Mieto and Manuela Di Centa. I can’t say that I’d ever heard any rumors about either skier in the past. As with every other post I’ve done on a skier accused of doping, this look at their results data isn’t meant to be an exercise in searching for evidence. Instead, it’s just an opportunity to go back and look at what they’ve done, so that we at least have a sense of how they actually performed.

Mieto, of course, mostly predates my complete data. Hopefully some day I’ll finish compiling the rest of the WC results back to the late 70’s (I’ve got around 60% of them at the moment). Even Di Centa’s career is only partially covered by my data. She did a handful of WC’s in her early 20’s, but her racing seemed to really pick up in 1988, and my data doesn’t really start until 1992. Regardless, here’s what we have:

1994 was the year she seemed to be really have “out of this world” results, relative to the field, and again to a lesser degree in 1996. Following that season, you can see her results tailed up significantly. Sandwiched in there is a seemingly “off” year in 1995. If we change our scales to finishing place, though, we see that that was an unusual season all around:

She only did five races that season, but three of them were top 5’s at the Thunder Bay World Champs. That was long enough ago that I can’t remember what was up with her that season. But she didn’t even race at the WC’s that December that were in Italy, and I don’t see her popping up in any other FIS races either. Seems like too short a window for her to have had a baby during the off-season (though you never know, women can be pretty amazing sometimes…). Or she could have been dealing with injury or illness.

And once again, this doesn’t really shed any light on doping accusations. It’s just an excuse to look at some results histories…

Tagged doping, manuela di centa, World CupThis post is somewhat of a teaser trailer for the sorts of things we can do once we have a complete record of major international ski results stretching back to the 70’s.

A natural and possibly controversial question is whether the World Cup field has become more or less competitive over time. Â Intuitively, I think it’s clear that it probably has. Â That’s just the natural progression of any sport as it attracts more money, sponsors and participants. Â The skiing community as a whole simply gets better at producing fast skiers.

But this process can make it difficult to compare the results of today’s athletes to those of many years ago.

In a sort of XC skiing data fantasy world, we’d like to make direct comparisons between modern skiers and historical skiers (i.e. is Petter Northug faster than Gunde Svan?). Â The only real way to answer that question would involve time travel. Â We can, however, make relative comparisons about the entire field. Â So we can ask the following: Is the average 30th place finisher on today’s World Cup closer to or further behind the winner than the average 30th place finisher in 1984?

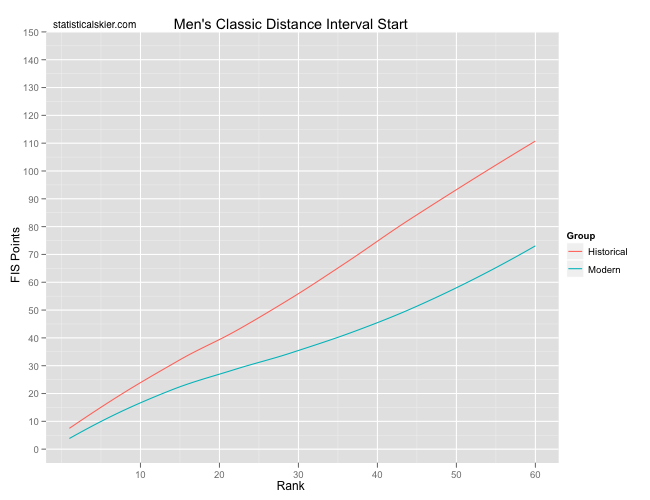

To do this I grabbed some preliminary data from my big data entry project. Â To keep the comparison and fair (and simple) as possible, we’re only going to look at men’s interval start classic races. Â (I think it’s pretty obvious that skating comparisons are going to be problematic.)

I happened to have all the results for World Cup races from the 1982-1983 and 1983-1984 seasons, so those races will serve as our “historical” data set. Â I’m assuming that all these races were classic races, which isn’t technically correct, if I have my history right. Â At least a few of these races had experimental “skating zones” where people were allowed to skate for a few hundred meters at a time. Â Personally, I think that’s a small enough deviation from “classic skiing” that for these purposes, we needn’t worry.

Next, we’ll take a roughly equivalent number of modern men’s interval start classic races. Â The result is around twenty historical races and twenty modern ones (from across the last several seasons, since classic interval start races are more spread out in the schedule).

The following graph shows the average FIS points (calculated using modern rules for all races) for both groups versus finishing place:

I was expecting the average modern skier to be closer to the winner, but I wasn’t expecting the difference to be this large or to range across the entire field like this.

I was expecting the average modern skier to be closer to the winner, but I wasn’t expecting the difference to be this large or to range across the entire field like this.

Now, World Cup point rules have changed as well. Â Back in the day, only the top twenty scored points, and the point scale differed. Â Still, we can make some sensible comparisons for the average 10th, 20th, etc. place finishers here.

For interval start races, FIS points are essentially just percent back times 800. Â This means that the average male 30th place finisher in the early 80’s was ~2.5% further behind the winner than today’s average male 30th place finisher. Â Two and a half percent! Â That’s probably almost a minute in a 15km and just over two minutes in a 30km.

Obviously, the point here isn’t that the skiers from back in the day were slow. Â Remember, we can’t say things like that because that would be a direct comparison. Â It’s just that when the sport was younger, there were fewer people able to ski close to the winner.

The way I like to think about this is to compare the World Cup circuit to a game of musical chairs. This entails reading the above graph “backwards”. Let’s start with a 30 FIS point World Cup result. If we move across horizontally from that spot on the y axis, we see that there were typically around 15 skiers in the early 80’s who were capable of finishing that close to the leader. Continuing across the graph, we can see that that number has increased to around 25 now. So you could think of that as adding 10 people to a game of musical chairs that started with 15 people and 15 chairs.

Tagged classic, history, interval start, men, World CupContinuing on from last time, we’ll single out a handful of skiers who appear to do significantly better in shorter sprint courses. Same methodology as before led me to pluck out the following three skiers:

In general, the effects in this direction tended to be weaker and less dramatic, even at the extreme ends of the distribution. Speculating wildly, I’d venture a guess that given the endurance characteristics in skiing, you’re just more likely to have people with skill sets that lend themselves toward longer distances, all things being equal.

Manificat isn’t necessarily known for his sprinting, but he seems to have done better (in qualification, at the very least) on sprint courses closer to 1km. I find that kind of interesting because I generally think of him as being stronger in longer distance races (i.e. 30km+) though I haven’t looked at any data to check that.

It’s tempting to dismiss Simonlater’s trend as being the result of those three shorter races. But even if you exclude them, you can see a fairly abrupt break in performance right at 1.4km. It’s verging on being a step function, rather than a continuous change. Weibel’s trend is the most marginal, in my view.

Tagged Analysis, caroline weibel, course length, maurice manificat, Sprint, timo simonlatser, World CupThe notion of an athlete preferring distance races of a particular length is pretty familiar, but what about sprinting? The differences between a 0.8km and a 1.8km sprint course may not seem like much compared to the differences between a 15km and 30km race. But (while I’m not a physiology expert) it seems likely to me that you could very well run into much more significant differences in the physiological demands at that smaller scale, in terms of what sorts of things your body needs to be efficient at.

That’s a long winded introduction to my having run through some simple linear mixed effects models that look at skiers who have a particular tendency to do better (or worse) in sprint races of different lengths. I’m going to start you off with the graph, which is fairly self-explanatory. But be warned, there will be quite a list of caveats…

The pool I’m drawing on here are folks who’ve done at least 10 major international (WC, OWG, etc.) sprint races. One tricky thing with sprints is what you use as your response variable. I’ve chosen four of the skiers who exhibited the strongest effect in one direction, towards better performance on longer courses. I’m using the final position (not qualification rank) here. In a lot of ways, looking only at qualification speed would be “cleaner”, but I wanted a measure that captured more than just one round of the event; a measure that reflected how well you actually performed in the sprint race as a whole.

Another big caveat here is that this graph represents all the athlete’s races, so we could be obscuring a confounding variable of changes over time. (I was particularly worried about that with Holly Brooks, but upon checking the raw data, that doesn’t seem to be the case.)

I’m going to start with Petra Majdic, because it’s a great opening into yet another factor that can be at play here. The effect of performing better on somewhat longer sprint courses for her is probably the weakest of the four. One interesting feature is the rather sharp cutoff at around 1.2km. Since Majdic is (was) one of the fields best sprinters, ever, how can we explain the apparent tendency to perform so much worse over shorter distances? Among many possible options, one things that comes to mind is that shorter courses will tend to make races more unpredictable. Being unlucky, in terms of crashes or stumbles, has a much larger effect. So we might expect less consistency from even the best skiers on shorter courses.

Holly Brooks is a somewhat dramatic example, particularly since so many of her results never went past qualification, so one could argue that we’re seeing something more directly reflective of her response to race effort length. On the other hand, our data for her are the most limited. Small sample size, and all that. The other two I’m not terribly familiar with.

On Thursday we’ll look at some folks with trends in the opposite direction…

Tagged Analysis, holly brooks, jeori kindschi, petra majdic, Sprint, valentina novikova, World Cup